The collaborative efforts of RUSTIK partners, including Francesco Mantino, Barbara Forcina (CREA Council for Research in Agricultural economics), Heidi Vironen, Liliana Fonseca (EPRC University of Strathclyde), and Petri Kahila (UEF University of Eastern Finland, Karelian Institute), have culminated in a comprehensive review of rural proofing instruments and experiences across both European and non-European countries. The complete report is accessible here.

In their examination, the report highlights concrete case studies which materialised the rural proofing concept in the formulation of policies and programs since the beginning of the millennium. While some national jurisdictions have achieved modest success, the report concludes that neither any country nor the EU as a whole can be deemed fully successful in integrating an effective and enduring rural proofing model into their administrative systems up to the present moment. To bridge this gap, the authors formulate the data and methodology needs to be tested within rural stakeholders in RUSTIK Living Labs.

What is rural proofing? Definition and policy relevance

The authors cite Jane Atterton, from the Scotland’s Rural College, who states that “Rural proofing is a systematic process to review the likely impacts of policies, programmes and initiatives on rural areas because of their particular circumstances or needs (e.g., dispersed populations and poorer infrastructure networks). In short, it requires policymakers to ‘think rural’ when designing policy interventions to prevent negative outcomes for rural areas and communities. If it is determined that a policy may have different – negative – impacts in rural areas compared to urban areas, policies should be adjusted to eliminate them”.

This concept was first introduced by a UK governmental publication in 2001 and was then included at EU level in 2016 in the Cork 2.0 declaration. Since then, regular mentions of the rural proofing mechanism are made in OECD and EU institutions’ strategies, reports and tools (Committee of the Regions in 2022) Rural proofing is also a pilar of the European Commission Long-Term Vision for Rural Areas, the new EU flagship initiative for Europe’s rural areas to which RUSTIK contributes to bring to the local level.

Comparing rural proofing characteristics in different countries

In most countries, rural proofing is applied to policy impact on living conditions and well-being in rural areas: this implies taking into consideration a broad range of policies (from infrastructures, social services to environment and business development). This ensures a good margin of flexibility to screen out those policies not having a significant impact and concentrate the proof only on relevant policies. In some countries, rural proofing is activated when specific rural territories could be impacted by policies. The table on the next pages portrays this well and expands on the specific methodology and guidelines used in the different countries where a rural proofing mechanism has been experimented.

Rural proofing mechanisms and attempts in EU and non-EU countries

Country |

Starting year |

Thematic focus |

Methodologies |

Institutional responsibility |

Application |

Proofing on a broad range of policies |

|||||

England |

2000 | National: Policies having impact on Infrastructures, services, working and living conditions, environment, equality | Checklist; Decision Tree; Examples of possible assessment; Descriptive assessment of impacts; Annual rural proofing reports | National: DEFRA (Department for the Environment, Food and Rural Affairs) oversees rural proofing across the government; Rural Affairs Board provides strategic guidance; each government Department has nominated ‘rural proofing lead’ | Mandatory (in principle) with patchy application |

Northern Ireland |

2015-2017 | All national policy proposals having an impact on the economic, social, cultural and environmental well-being of rural communities | Rural needs impact assessment: coherence of likely impact with social and economic needs of rural areas; annual monitoring reports | National: Department of Agriculture, Environment and Rural Affairs (DAERA) | Mandatory (in principle) with patchy application |

Canada |

1998-2013 | National: Federal policies and programmes from the perspectives of remote and rural regions. Some provinces have published their own Rural Lens and guidelines. | Checklist; Rural Lens: process in 10 stages, including a template to fill, questions to answer and examples to follow. Guidelines for using it provided by the national level. | “Rural Secretariat” within the Department of Agriculture and Agri-Food (founded in 1996) | Voluntary, no sanctions |

New Zealand |

2008 | Policies having impact on infrastructure, health, education, business development and equity | Impact assessment checklist; process in 7 stages; Rural proofing guide; | Ministry for Primary Industries published the guide and checklist. The implementation lies with the authorities responsible for a specific policy. | Voluntary, no sanctions |

Proofing on specific geographical/ thematic areas |

|||||

Scotland |

2020 | Policies with specific and differentiated impacts on Islands Communities | Island Communities Impact assessment | Agriculture and Rural Economy Directorate and its Cabinet Secretary for Rural Affairs and Islands | Mandatory (with justification for not doing it) only for policies having effects on Scottish Islands |

Finland |

2007 | National: Policies having impact on municipal merging, rural livelihoods, expertise, housing and services, accessibility, attractiveness factors and community cohesion. Emphasis ono sparsely depopulated areas. | Checklist, with 6 thematic areas and flexible application | Rural Policy Council (MANE) under the Ministry of Agriculture and Forestry (MAF) | Voluntary, no sanctions. Formalisation into legislation is being discussed in the Parliament. |

Australia |

2003 | Regional services | Checklist; Regional Impact Assessment Statement (RIAS) Standardized guidelines as a template | Department of Primary Industries and Regions of the Government of South Australia (PIRSA) | Mandatory, for any legislation affecting regional services |

USA |

2018 | National for drug addiction in rural areas | Rural Community Action Guide with best practices; Federal Rural Resource Guide with key challenges; Rural Community Toolbox website with all federal fundings and tools to build healthy drug-free rural communities | The Office of National Drug Control Policy (ONDCP) of the White House develops Federal drug policy and coordinate its implementation across the Federal Government. | Political rather than a legislative commitment, and it is not mandatory. |

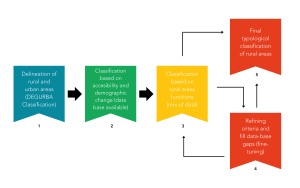

Lessons learned for RUSTIK experiments

To conclude, rural proofing is strongly focused on policy assessment, whether spatially focused policies or not. This implies the definition of an appropriate list of questions to be explored and, in parallel, specific data concerning potential policy effects upon the concerned Living Labs of the project. For this, the deliverable lists the questions forming the basis for a place-based analysis depending on the types of policies considered. Moreover, the authors explore the necessary conditions for a successful data collection leading to robust evidence-based territorial policies and applying rural proofing mechanisms. All these elements will be practically explored in coordination with the RUSTIK Living labs from the end of 2024 onwards.