Garfagnana, Italy

Key Facts

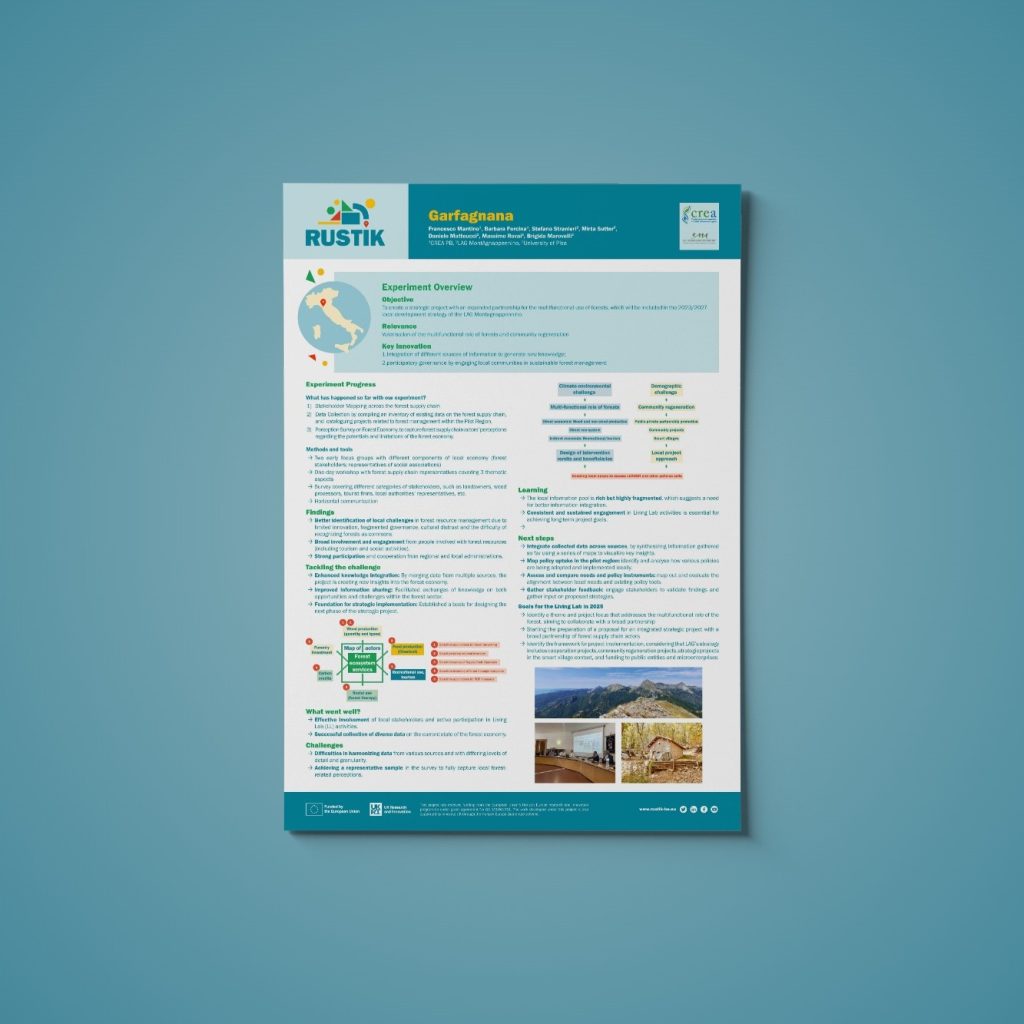

The local action group Montagnappennino is based in the territory of Garfagnana, Media Valle del Serchio, Alta Versilia and Appennino Pistoiese. four geographical areas are part of the provinces of Lucca and Pistoia in the northwestern Tuscany, for a total territory of 2110 km2 (1872 mountainous) and including 27 municipalities.

Morphologically, the Garfagnana and Media Valle del Serchio areas (central part of the territory) are structured around the Serchio river system and the mountain systems that flow into it, namely the Apuan and Apennine systems, which are characterized, in turn, by deep transverse valleys. The Alta Versilia area is composed by 2 municipalities in the Apuan Alps (western part) and the Montagna Pistoiese area by 4 municipalities in the Appennine (eastern part). The area offers a wide variety of landscapes, starting with an impervious and unspoiled mountainous belt, rocky in the Apuan Alps, meadowy and a gentler slope in the Apennines, which transforms at the lower altitudes into a hillside rich in meadows and cultivated fields of particular scenic beauty. The course of the Serchio River with a wide pebbly shore everywhere marks the centre of the valley’s slope.

The highest peak in Tuscany, Mount Prado (2054 m), lies on the border between Garfagnana and Emilia-Romagna, while the highest peak of the Apuan Alps, Mount Pisanino (1947 m), is located entirely in upper Garfagnana.

The area called Montagna pistoiese is located north and northwest of Pistoia, on the southern ridge of the Tuscan-Emilian Apennines and extends from Alpe delle Tre Potenze (1940 m), which dominates the Val di Luce and part of the Abetone ski area, to the eastern slopes of Mount La Croce (1318 m), near the Acquerino Forest. Bordered to the northwest by the province of Modena and to the north by that of Bologna, it has some differences between the markedly alpine western part and the morphologically gentler eastern part, typically Apennine and characterized by elevations of no more than 1300 mt., separated by the Reno valley.

Major weaknesses are population decline, a population density of half the regional average, and a high age and dependency ratio of 57% of the population.

The total population in the area in 2020 was 88,343, while in 2001 it was 96,556. The demographic data confirms the steady trend of population decrease. From 2011 to 2020 there was an overall decrease in the area’s total population of -7.58%, with a difference between the Lucchese area.

Data as of 2019 on population structure show that in the area, the population over the age of 65 accounts for 29 per cent of the total, up more than one percentage point from 2014, where it stood at 27.81 per cent. This value marks a consistent deterioration from the figure eight years earlier, in 2001, where the percentage was 24.8 per cent. In 2019, the population over the age of 85 represented 5 per cent of the total in the province of Lucca and 6.74 per cent in the province of Pistoia, still up from the 2014 data where some municipalities already had even higher percentages.

Living Lab transitions

As for the breakdown among the various sectors of activity, around 12% of local units are in agriculture, 30% in industry and 58% in other activities. Within these, the “trade” sector weighs almost half, and in the total number of local units, it accounts for 26%. Agriculture has a higher percentage incidence in the province of Pistoia (16% of local units) than in the province of Lucca (11% of local units).

Businesses registered with the Business Registry of the province of Lucca as of 12/31/2019 totalled 42,714, 167 units (-0.4 per cent) lower than the figure recorded at the end of 2018. The decrease confirms the continuation of the long wave of the economic crisis that began in 2008 and has manifested itself with alternating phases until today.

The socio-economic environment, but above all the social conditions, human relations and any community, has been severely tested throughout 2020 and 2021, as the short period of restrictions did not allow for full recovery, but rather dragged on, exacerbating previous critical issues.

The choices made for managing the COVID-19 emergency, have drastically and abruptly, without any possibility of putting in place preventive policies of progressive management of the state of emergency, changed the benchmarks in every sector of our communities. Many businesses have reworked their strategies and communities have sought new balances and started socio-economic experiences within their social environment, initiatives that were, however, always limited by restrictions that could not be fully expressed. The community was confirmed as a fundamental element, a potential place for sharing, contamination, integration, and planning. The animation activity of the new LEADER-specific action sheet “Community Regeneration Projects” was developed in this context in the second half of 2021, trying to capture what was already spontaneously moving and to stimulate responses in this direction.

The strengths remain in the area’s structural elements, i.e. history-environment-culture-traditions-agro-livestock and gastronomic specialities. Strengths are a strong identity link between artisanal productions, agri-food and local knowledge, historical-architectural, landscape, the naturalistic context of good quality to support the quality of the residency and tourist attractiveness; availability of real estate assets in historical centres for residential use and tourist accommodation activities; the widespread presence of an associative and voluntary vocation; the presence of socio-cultural experiences potential elements of contamination and inclusion.

Major critical issues are the uneven territorial distribution of commercial services, especially to the detriment of historical centres, poor generational renewal in entrepreneurial realities due to demographic fragility, reduced attractiveness of the territorial context to new investments, degradation of historical centres and the landscape context, distance from services for residents in noncapital centres, reduced level of entrepreneurship in the social sector, strong criticality in the transfer of good practices to support young entrepreneurs and innovation in companies.

In the territory of the LAG area, there are two park areas (the National Park of the Tuscan-Emilian Apennines and the Regional Park of the Apuan Alps) with a total area of 1,946 hectares and 13,758 hectares respectively. In addition, there are 8 State Reserves (4 in the territory of the province of Lucca and 4 in the territory of the province of Pistoia) with a total area of 2,227 hectares.

A recent element that further characterizes the environmental-landscape context is the recognition as a UNESCO MaB Reserve of the territories of the National Park of the Tuscan-Emilian Apennines. This represents a remarkable opportunity in that the territory will be able to enter the process of developing the branding of Biosphere Reserves applied to high-quality food products and their use in gastronomy.

The strengths are good structuring of the local nature network (parks, protected areas, hiking trails…), high and widespread agricultural biodiversity (ancient varieties) that can allow their recovery and valorisation for the creation of “niche” markets with high added value, high know-how for the conservation of germplasm of ancient breeds and varieties (Regional Germplasm Bank Nursery La Piana).

Weaknesses are the sharp contraction of Agricultural Land Area due to widespread abandonment and denaturalization phenomena, a reduction in the number of people employed in agriculture.

The potential represented by plant and animal biodiversity, a consolidated culture and action of local, national and transnational experiences, recovery and conservation of animal and plant species, their introduction in the open field, and the quality of primary and processed products related to them, can be a starting point from which to overcome the shortage of agricultural land and the difficulties inherent in the geomorphological structure of our territory.

Regarding digitalization, the rural population’s lack of digital skills and the low percentage of households with access to fast broadband: 47 per cent in rural areas versus 80 per cent in urban areas. There is a lack of professional training in digital tools, and it is hard to bring stakeholders together because the tools to improve cooperation are not sufficiently developed.

The policy recommendations are to develop a participatory design of digital solutions through a multistakeholder process that must be interactive and people-centred. The approach must generate a platform for stakeholders to drive innovation forward with some principles: involvement, democratic decision-making, dialogue, and consensus.

Some of the policy alternatives present in the area:

Cooperation between stakeholders: many single initiatives, lack of cross-sectorial cooperation. Individual websites are used for agritourism – part of the booking, Airbnb; but there is a lot of skills gap, which reduces the profit margin. Also, QR Codes to get feedback from guests are not well maintained.

In the past years, funds were available from the Local Action Group, but there isn’t any project application under the theme of digitalisation.

Unfortunately, the magnitude and sign of this transformation are only partially taken into account by those designing, adopting, or funding digital technology-based innovation. If applied on a large scale and without compensatory action (e.g., retraining and relocation of the workforce) or preventive action (legislation to regulate the use and ownership of data), automation can generate (in part has already generated) disruptive social effects, such as unemployment, loss of autonomy, and invasion of privacy. Moreover, unequal access to connectivity creates divisions between those who are connected and those who are not, widening social inequalities and increasing power imbalances.

Documents

Pictures 📸